This story was originally published in the Winter/Spring 2022 issue of Appalachia Journal.

Topsoil lies thin on the ancient slopes of The Western Catskills. As the locals say, it’s two rocks to every dirt. Given that and a downpour during a sudden thaw, or a dry spell, flash floods on the Neversink River can happen at any time. My mother and I almost got washed away by one in late July 1969. We were on our way home to Claryville when the river swelled past the guardrails and came up to our car just before the bridge to Hunter Road. We lost traction and began to drift sideways, almost going into the river before our rear wheels caught something that pushed us back on the road. We were lucky. In that same spot, a flood in October 2010 swept a Willowemoc resident off the bridge as she was driving to work before daybreak. The state troopers recovered her body on the shores of the Neversink Reservoir. They found her Honda Civic “crumpled like tinfoil,” as the accident report put it, on a sandbar upstream. Since 1951 when the U.S. Geological Survey began keeping records, seasonal changes in water volumes on the Neversink have been extreme, even for a Catskill river.

“Neversink” is a corruption of nkëchehòsi sipu, meaning “crazy river” in the Lenapé tongue of the watershed’s original inhabitants. The logging and farming practices of the European settlers did nothing to calm it down. In my lifetime, the Neversink’s West Branch, where my family has been for generations, confirmed that reputation many times. In a rage, the clear waters swell to a torrent of red mud, coursing down the valley at 20 knots or more. At peak force, I can hear the rumble of boulders creeping along the riverbed.

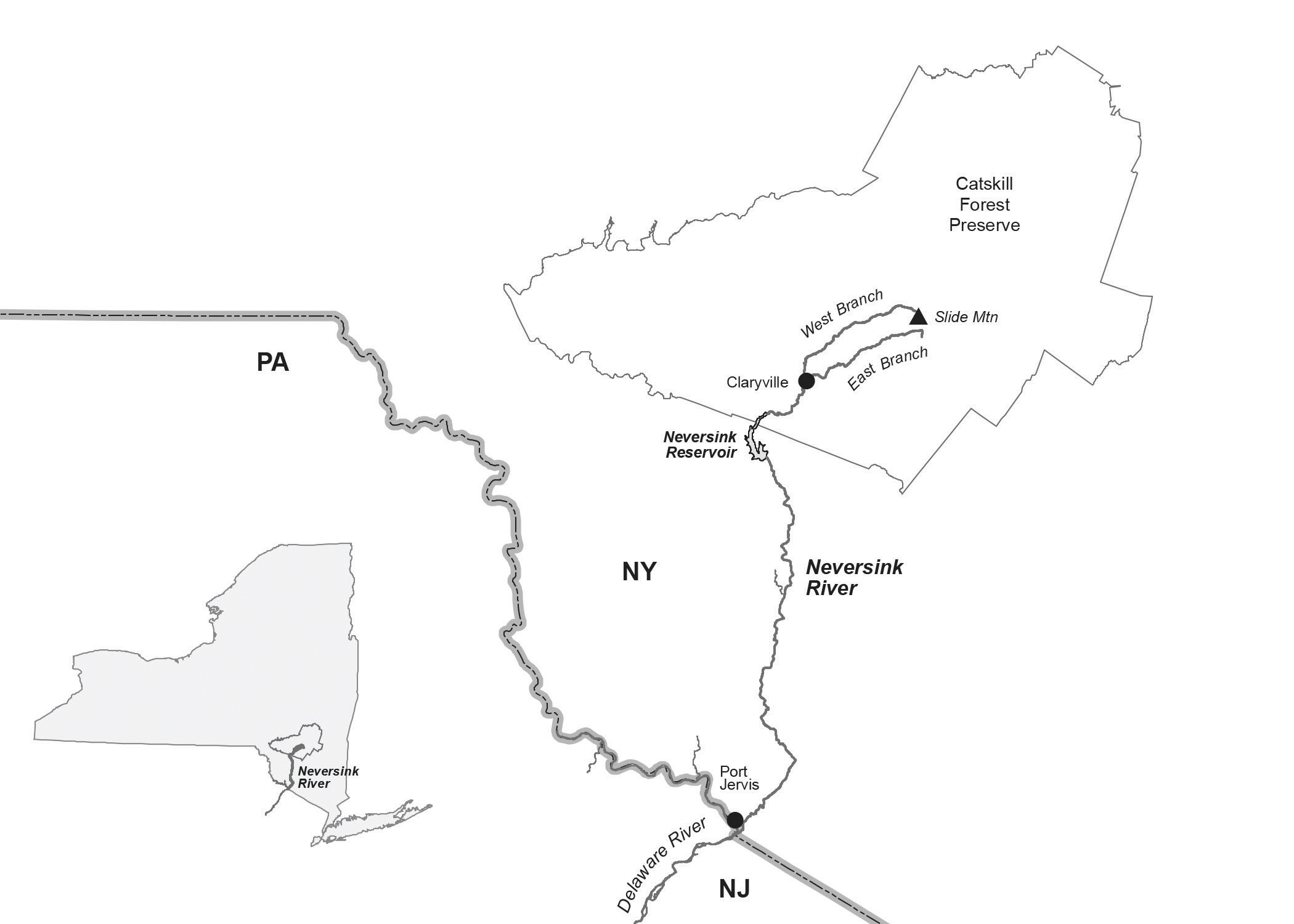

The West Branch springs from the northwest flank of Slide Mountain, the tallest peak in the Catskills, and runs fourteen miles east to west through Frost Valley.

The West Branch meets the East Branch at Junction Pool to form the Neversink proper, which washes into the Delaware River. The West Branch has shaped my life as surely as it has worn the outcroppings of blue slate and red shale that punctuate its length. It carved out some of my earliest memories: roaring waterfalls, shivering limbs, and slippery stone at Leroy Pool, where my extended family would congregate in summer. When I was 3, I came close to drowning by falling into Leroy’s upper falls. Pinned by the powerful current, I remember feeling stunned, floating on my back while blinded by the sun refracted through the rushing waters. My Aunt Barbara saved the day. A former lifeguard, she dove in and pulled me by the hair onto the rocks.

No one remembers Mr. Leroy and his family, who farmed that land, grazing their cattle and sheep over a hundred years ago. Only the pool remains, part of a bequest of five square miles from Clarence M. Roof, a wealthy importer from Cooperstown, New York, to my grandmother, Jenny Franklin Connell, née Hovey, upon his death in 1923.

Before the European settlers wrested away the land from the Lenapé, virgin hemlock covered the Catskills. Witnesses to the glaciers’ retreat from the Northeast 10,000 years ago, virgin hemlocks were the dominant plant of the early Holocene. Some old growth still endures on slopes that are too steep or remote for logging. As hemlocks’ dense canopy keeps the understory dark and mossy, hemlock is keystone species for the Catskills. Hemlocks’ riverside impact on the West Branch keeps the water several degrees cooler than that of the neighboring East Branch. At Leroy Pool, hemlocks crowd the south bank of the rocky basin. Once, when I was gazing at them from the rock cliff at the pool’s edge, their blue-green needles gave me the impression I had entered a Maxfield Parrish painting. Now the woolly adelgid, an invasive species from East Asia, threatens the hemlocks’ survival. The woolly adelgid is but one of many insects, stowaways of international shipping, that have no native predators in ecosystems east of the Mississippi. Others include the spotted lanternfly, the emerald ash borer, the Asian longhorned beetle, and the brown marmorated stink bug.

By the mid-nineteenth century European settlers had cut down most of the hemlocks to use their bark for tanning leather, a lucrative enterprise that lasted as long as the trees did. The other deforestation culprit was the so-called merino craze, which came to America after the Napoleonic Wars, when the merino breed of sheep spread from Europe. The explosion of shepherding completed the shift from forest to open pasture. Because of the forest loss, new channels and floodplains eroded what little topsoil the Frost Valley had and introduced sheep manure to the river, increasing plant and insect life. As more productive regions emerged out West after the Civil War, shepherding died out in upstate New York and New England, but the damage was done. The first-growth hemlocks were no more.

Over my grandmother’s lifetime, the Catskills reforested with second-growth hardwoods—maples, cherry, ash, birch, and, on the lower reaches, oak. These did little to mitigate the loss of hemlocks, which had destabilized the West Branch and allowed the river to sweep from one side of the valley to the other, grinding boulders to rocks, and rocks to sand. For most of the twentieth century, the water cycle fell into something like a pattern: the quiet of winter’s ice, spasms of spring thaws and summer floods, the steady procession of fall rains through October and November.

And then, in the second decade of the 21st century, the pattern broke. Two back-to-back “100-year floods” tore apart the southwest Catskills. One was Hurricane Irene in 2011. The second, in September 2012, was even more damaging, a nameless local rain bomb that dumped between 9 and 10 inches within a 24-hour period. In the Sullivan County Democrat, Neversink town supervisor Mark McCarthy said at the time, “It was worse than Irene.” Both floods swept away power lines, roads, bridges, and anything else that stood in their path. After the rain bomb, the water table was so high people in Frost Valley and nearby Claryville couldn’t use their septic systems for days.

As for the West Branch, the massive water columns generated by Irene and the rain bomb had dug trenches through Frost Valley, tearing out the vegetation and leaving silt along the riverbanks. What the water columns also left behind were uprooted trees, sections of road, scrap metal, piles of rocks, and trash everywhere. These twin disasters were much more than the typical spring, summer, and fall floods we had come to expect from one year to the next. These weather events threatened the infrastructure—electricity, roads, telephone, internet—we took for granted. I had read about dying coral reefs, the thawing of the permafrost in the Arctic, droughts and wildfires in California and Australia, and many extinctions. But climate change had come to my valley.

When I surveyed the 2012 rain bomb’s damage to the river, my body froze like that 3-year-old paralyzed by the weight of Leroy’s falls. Fear lodged in my mind like a spike, a golden spike for the Anthropocene, the dawning geologic age precipitated by the changes our species has visited on the earth’s surface: air, water, and ground pollution; the disturbance of the water cycle; the destruction of animal habitat through farming and logging; mass extinctions; ocean acidification; and unprecedented concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, refrigerants, and other gases. The extreme weather of the rain bomb had a human origin, the result of an equal and opposite reaction to industrial civilization’s attempt to bend the natural world to its will. Nations, corporations, and the general population had ignored the warnings and mounting evidence since the 1960s that climate change was an existential threat, and now here I was witnessing the catastrophic repercussions from that indifference.

A golden spike is a marker in a rock layer set by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) that establishes the beginning of a geologic age—identified by the lowest boundary they’ve found, the smallest stratigraphic interval in the world’s succession of rock layers, or strata. A golden spike marks geologic time. It ratifies stratigraphic evidence at a specific location for the beginning of a stage, which is the equivalent of a geologic age. In 1977, when I was in college in New Jersey, a bronze plaque in a rock outcrop-ping near the Czech village of Suchomasty established the 419-million-year-old boundary between the Silurian and Devonian periods of the Paleozoic era. It was the ICS’s first golden spike or Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP).

Since 1977, the ICS has placed 75 golden spikes all over the world. The oldest, in South Australia, goes back 635 million years to the Ediacaran Period, which preceded the Cambrian explosion of multicellular organisms. Geologists have differentiated the ages in rock layers by identifying index fossils, whose presence indicates a stratigraphic stage. Index fossils by definition have limited vertical range in the geologic record and have a wide geographic distribution. The index fossil for the golden spike near Suchomasty was Monograptus uniformis, a filter-feeding marine invertebrate resembling a tube worm. Going back 372 million years, the index fossils for the upper Devonian shale deposits in the West Branch of the Neversink are conodonts, jawless fish related to the modern lamprey. Montagne Noire, located in the southwest of France’s Massif Central, has the world’s golden spike for that geologic age. Trout, the fish that made the Neversink famous in John Burroughs’s essay “Speckled Trout,” are descended from salmonids that evolved 88 million years ago and therefore newcomers compared with conodonts. After befriending Burroughs at Yama Farms, the resort in Napanoch, my grandmother let him fish her stretch of the West Branch more than once. She said he smelled like a tree.

Other ways to measure stages in stratigraphy include analysis based on changes in magnetic polarity, the composition of rocks, and radioactivity. The ICS has yet to place a golden spike for the Anthropocene in any location because stratigraphers cannot agree on when it began, or what the evidence for it would be in the geologic record. Biologist Eugene Stoermer coined the term in the 1980s, but atmospheric scientist Paul Crutzen popularized it in a paper he published in 2000. The beginning of agriculture 12,000 years ago, the rise of European colonial powers in the sixteenth century, and the dawn of the industrial age in the late eighteenth century are all candidates. The strongest contender appears to be the Manhattan Project’s Trinity Test in 1945, as it marked the beginning of atmospheric thermonuclear weapons testing, which left on the earth’s surface a singular footprint of plutonium, carbon-14, and other isotopes. For now, the Anthropocene lives in an ideational limbo, perhaps favored more by academics in the humanities than earth scientists. Although the ICS has not arrived at a consensus, I know when my Anthropocene started: September 18–19, 2012, when the rain bomb hit Frost Valley. The golden spike isn’t located in any rock face but in my body, where I carry within the strata of my memory the trauma, which millions now share, of human-induced extreme climate events.

Just as heat-trapping gases threaten our world, catastrophic rises in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, caused by massive volcanic eruptions across what is now Siberia, triggered the Permian–Triassic extinction 250 million years ago. Marking the end of the Paleozoic, it was the greatest mass extinction in the earth’s history. The Great Dying, as it is known, bears a striking similarity to the present climate crisis. The acidification of the oceans, the rise in surface temperatures, oxygen deprivation—all things happening now to our air, land, and water—led to the extinction of 90 to 96 percent of all marine species, and 70 percent of all terrestrial vertebrates.

The Permian–Triassic event lasted between 100,000 and 150,000 years. What is unique, and frightening, about our time is the increase in greenhouse gases during the last 50 years—an instant by geologic standards—as more and more humans adopt the energy-intensive ways of the industrialized nations. Unless we change course, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere—never mind methane, which is 30 times more efficient at trapping heat—will rise well above current levels of 400 parts per million in the next 50 years. The earth hasn’t seen 400+ ppM since the Miocene, 15 million years ago, when the oceans were 100 feet higher and temperatures 4 to 5 degrees Celsius warmer. Those sea levels and temperatures will render the tropics and current coastlines uninhabitable. Without drastic action, the climate crisis will cause our global civilization to crumple like so much tinfoil, and it won’t be just our species in the wreckage.

Looking out my window at the feminine curves, as my grandmother put it, of the Catskill Mountains rising above the West Branch, I see a forest painted red by the light of the setting sun. How many trees will die off if carbon dioxide levels continue to soar? What will happen to the animals? Will Frost Valley become a slimescape of death and decay, a feast for fungi and bacteria, as happened in the Great Dying? I don’t think so, but there’s no returning to the status quo ante. The time for mitigation was a generation ago. We are now in the danger zone of tipping points like the melting of the permafrost, which could release millions of tons of methane, or the Amazon forest, the largest terrestrial carbon sink, drying up to become grass-lands. If we are to survive, we will have to commit to ever more elaborate and unpredictable interventions in the planet’s land, water, and air cycles. I think about the enormity of what I am handing down to my two daughters, and I remember those long seconds when my mother and I got carried away by the flood waters.

Hovey Brock is an artist, educator, and writer who divides his time between Brooklyn and Claryville, New York.

If you enjoyed this article, please visit Appalachia Journal for more stories.