The Presidential Range in the White Mountains of New Hampshire is one of the most iconic mountain ranges in the United States. It comprises thirteen mountains, nine of which are over 4,000 feet in elevation, and seven of which are named after U.S. Presidents. One of the most challenging hikes in the White Mountains is the Presidential Traverse. It stretches 23 miles across the seven presidential 4,000-footer peaks and involves nearly 9,000 feet of elevation gain. But how and why were some of these peaks named after U.S. presidents? As it turns out, the names were assigned rather arbitrarily.

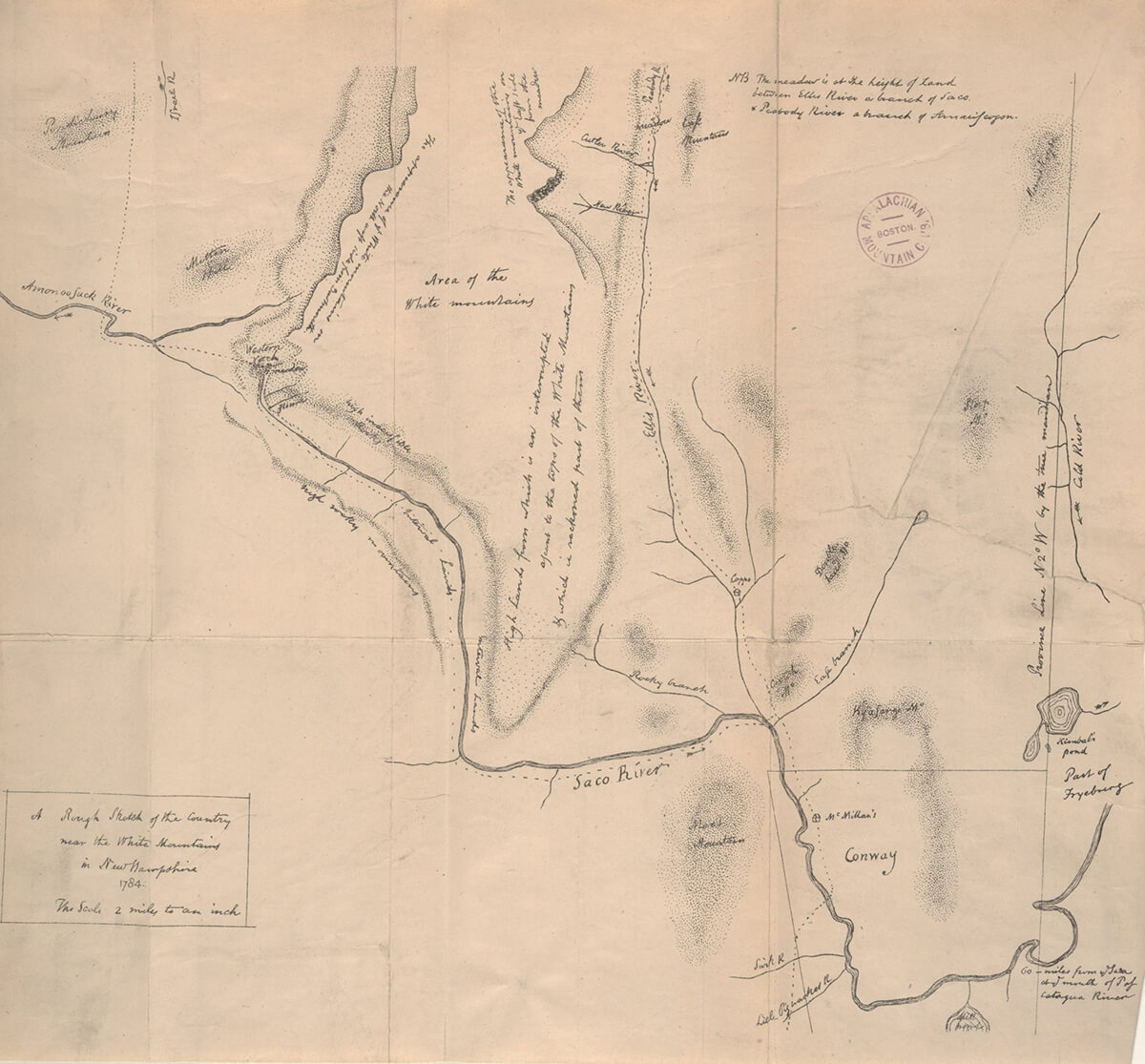

The first peak to be named was Mount Washington, though the exact date and the occasion of the naming remains unknown. The generally accepted theory is that the mountain was named by Reverend Manasseh Cutler sometime after his expedition to the peak with Reverend Jeremy Belknap in 1784. Belknap and Cutler were both prominent intellectuals at the time – Belknap was a Harvard graduate, minister, and historian who wrote the first history of the state of New Hampshire – and Cutler was a lawyer, minister, and early scientist, who was considered to be an innovative botanist. Though Belknap and Cutler were not the first to ascend Mount Washington, their expedition was the first well-documented climb in North America to gather information on natural history and measure the summit’s altitude. This trip was also one of the first times that scientists visited and observed a world above treeline in the United States.

In their written accounts, neither man actually referred to Mount Washington by a name. Instead, they called the peak “the great Mountain,” “the Mountain,” “the highest Mountain,” “Sugar loaf,” and “the White Mountain.” It was not until 1792 that the words “Mount Washington” appeared in writing, though the Belknap-Cutler expedition is thought to be the catalyst for this name designation. At the time, everyone was rushing to name things after America’s favorite General (and later, the first president of the United States), George Washington. Mount Washington’s original name, given by the Abenaki Indians, is Agiocochook, which translates to “Home of the Great Spirit.”

The rest of the Presidential Peaks were named in a single day in 1820. During the summer of that year, a party from Lancaster, New Hampshire set out to explore the range. This party consisted of prominent Lancaster residents who viewed themselves as pioneers. John Wingate Weeks (a New Hampshire Representative in Congress) and John Wilson (a former military general) were among the group. As were Adino Nye Brackett (a skilled surveyor and an active participant in town government), Charles J. Stuart and Samuel A. Pearson (two lawyers), and Noyes S. Dennison (an innkeeper). Phillip Carrigain (New Hampshire Secretary of State from 1805 to 1810 and a skilled mapmaker for whom Mount Carrigain is named) also joined the hikers. This party arrived in the area in July of 1820 and enlisted Ethan A. Crawford as their guide.

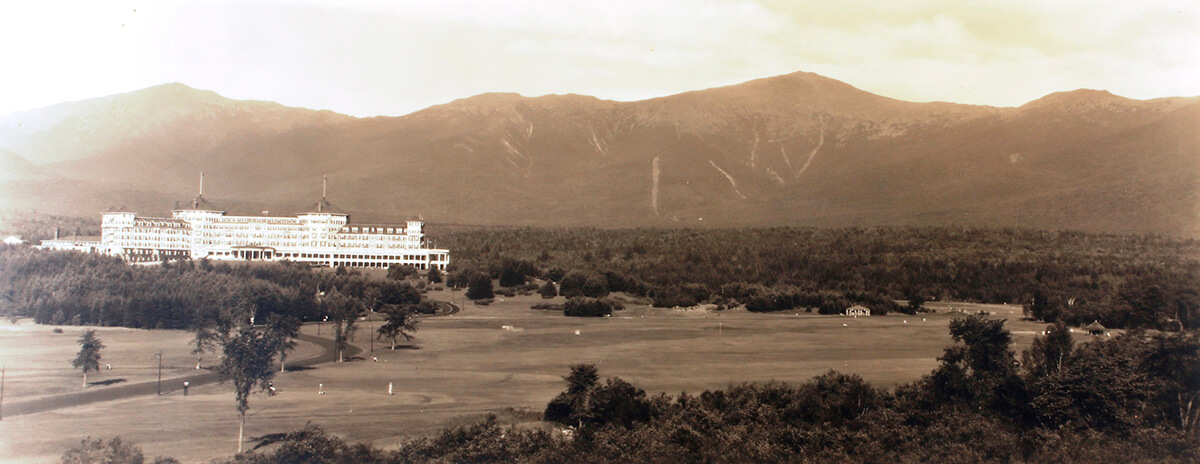

Crawford was known at the time as the “Mountain Giant” and owned and operated an inn near the heart of Crawford Notch – where AMC’s Highland Center now stands. The first substantial wave of White Mountain tourists were guided up Mount Washington by the Crawford family, and the first trails to receive regular and frequent use were cut by the Crawfords. Ethan Crawford in particular was regarded as quite the mountaineer. On his various guided trips, he was said to have carried a few fatigued people off the mountain when they couldn’t go any further. In a book titled Historical Relics of the White Mountains: Also, a Concise White Mountain Guide written by John Spaulding, he notes: “It was no uncommon affair for [Ethan] to shoulder a man and lug him down the mountain.”

Due to his expertise in the region and his mountaineering skills, it came as no surprise when the Lancaster party arrived at Ethan Crawford’s house, hiring him as a guide and baggage-carrier. According to a journal by Adino Brackett, Ethan carried nearly all of the gear for the trip: “They made Ethan their pilot, and loaded him with provisions and blankets, like a pack-horse; and then, as they began to ascend, they piled on top of his load their coats.” They traveled until they reached their camp for the night, where Ethan struck up a fire, prepared supper, and laid out everyone’s blankets. After exchanging stories, they all fell asleep. The next morning, they set out again, taking enough provisions for the day and plenty of “O-be-joyful,” which was slang at the time for a type of bootleg whiskey.

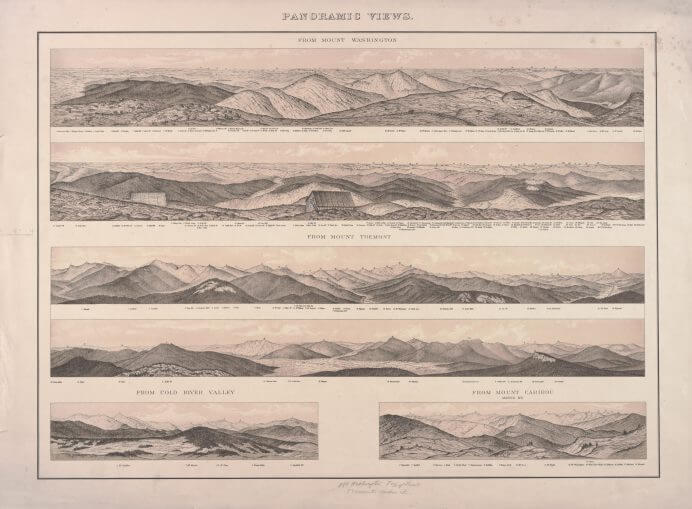

After ascending several of the mountains, they came to a beautiful pond, today known as Lake of the Clouds, which they named “Blue Pond.” After stopping by the water, they went on to the summit of Mount Washington. According to an account by Lucy Crawford, Ethan Crawford’s wife, it was here that they named the rest of the peaks that they could see: “There they gave names to several peaks, and then drank healths to them in honor to the great men whose names they bore and gave toasts to them.”

The process for naming these peaks was simple. As Mount Washington was the tallest peak named after the first president, the next tallest peak was named for the second president, John Adams, and so on. After christening Mount Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, the party ran out of presidents, but they still had two peaks remaining. They named one Mount Franklin, after Benjamin Franklin, and the other Mount Pleasant, though no one seems to know how this name came to be. Mount Pleasant was later renamed Mount Eisenhower by a vote of the New Hampshire legislature in 1969.

Without any specific protocol for naming peaks or any formal organization at the time (i.e. the United States Geological Survey), the use of these names seemed to spread by word of mouth in local and nearby communities. Though several of these peaks had indigenous names attached to them, many people still viewed them as “unnamed” until that day in 1820. However, it took a while for these names to appear on maps. One of the earliest maps printed with these presidential names was Franklin Leavitt’s tourist map of the White Mountains from 1852.

The remaining peaks in the Presidential Range were named in the 20th century. Mount Pierce, originally called Mount Clinton, for DeWitt Clinton (who served as New York’s Governor from 1825-1828) was designated as Mount Pierce in 1913. The sub-peak of Mount Adams was named for John-Quincy Adams, but it’s not exactly clear when that was assigned.

The rest of the peaks were not named after presidents. Mount Webster was named after Daniel Webster (a lawyer and U.S. Congressmen), Mount Jackson after Charles Thomas Jackson (a prominent geologist), Mount Sam Adams, after Samuel Adams (one of the Founding Fathers of the United States), and Mount Clay was named after Henry Clay (another U.S. Congressmen). There was an unsuccessful attempt by the New Hampshire State Legislature to rename Mount Clay to Mount Reagan in 2003, but the United States Geological Survey didn’t accept and it remains Mount Clay to this day.